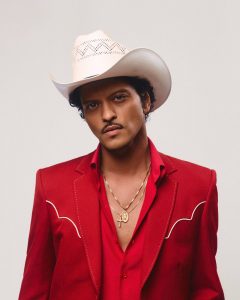

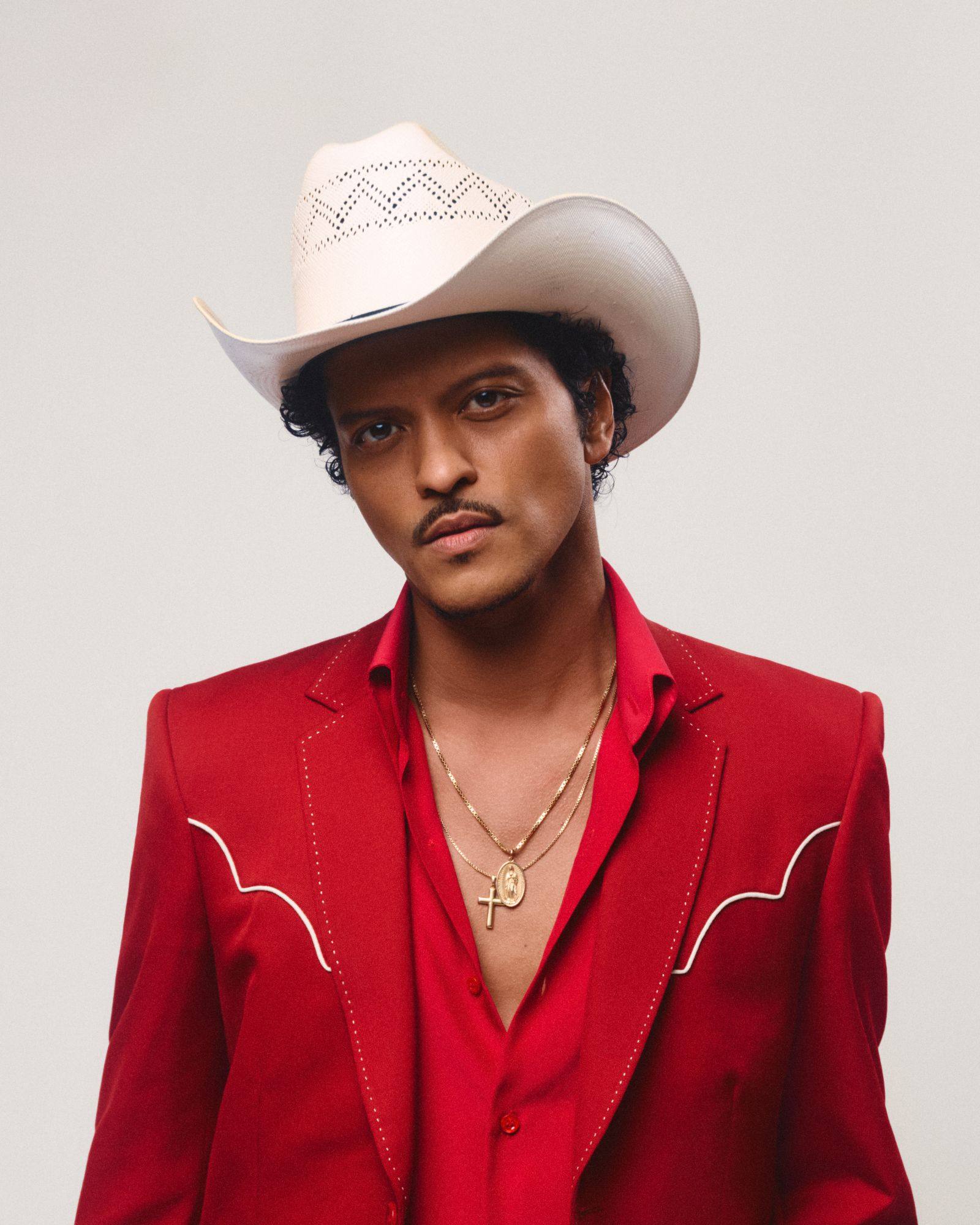

Chiara Ciccarelli blends global cultural experience with cutting-edge design at MAD Architects. From Rome to Milan, Amsterdam to Barcelona, she combines emotion, AI-driven exploration, and nature-inspired futurism to create architecture that connects people and environment in meaningful ways.

FM42: Your background spans Rome, Amsterdam, Barcelona, and Milan. How have these different cultural environments shaped your architectural approach and creative identity?

Chiara Ciccarelli: In many ways. I believe that for an architect it is essential to understand different worlds and, before that, to cultivate the ability to observe and listen. Architecture is ultimately a response to human behavior, so understanding why people act, move, and interact according to a certain culture becomes fundamental for me. Each city I’ve lived in has shaped a different layer of my creative identity.

Studying in Barcelona exposed me to a city where architecture is inseparable from its public life. From Gaudí’s organic imagination to the clarity of Cerdà’s grid, Barcelona taught me that urban form can be both visionary and deeply human. Its approach to public space—vibrant, social, and scaled to people—still influences the way I think about buildings as part of a larger organism.

As a complement, working in Amsterdam introduced me to a very different architectural mentality: pragmatic, democratic, and highly conscious of sustainability. Designing in a country that sits largely below sea level teaches you immediately that complexity is not an obstacle but a condition that can be addressed if well planned. The Dutch approach demonstrates how clear strategy and precise thinking can transform vulnerability into resilience.

Before all this, my studies in Rome and Milan, two cities that could not be more different in mindset and history, grounded my understanding of architectural identity.

In Milan, I encountered design culture as a form of experimentation. Milan is fast, contemporary, but overall ambitious. This ambition is rooted in its history: the city transformed itself into a major commercial and agricultural hub by engineering and expanding the Navigli system to connect lakes and rivers for transporting goods and to irrigate the countryside. The Darsena still bears witness to Milan’s vision of becoming an inland port, a hub for the surrounding areas. Rome, on the other hand, gave me a sense of continuity—an awareness of architecture as a dialogue across centuries, where layers of history coexist and inform the emotional resonance of space.

Together, I guess, these experiences are shaping and further shaping an architectural approach that is culturally aware, emotionally guided, and open minded.

FM42: MAD Architects is known for its futuristic, nature-inspired language. How do you translate these principles into your own design thinking and daily practice within the studio?

Chiara Ciccarelli: Working at MAD means approaching every project with a mindset that looks beyond form and function and toward emotion, atmosphere, and the relationship between humans and nature. One of the most meaningful lessons I’ve learned here is how differently this relationship is understood in Eastern and Western cultures. What inspires me in MAD’s approach is the idea that nature is not only a physical environment but also a spiritual and emotional dimension—and that architecture should exist in continuous dialogue with it.

In much of Western discourse, nature is often treated instrumentally: something to protect, manage, or measure. At MAD, I’ve encountered a perspective rooted in traditional Eastern thought, where nature is also a mental construct, a space of imagination. In Chinese landscape painting or in classical gardens, mountains and rivers are not literal depictions but expressions of an inner vision; they externalize a spiritual world. This has influenced the way I approach design: it is not only about how a building works, but about how it feels, what it evokes, and the emotional journey it creates for its users.

Cultural differences within the studio constantly push me to question the assumptions I grew up with—sometimes in challenging ways, but more often leading to discovery. MAD’s process begins with questioning conventions and imagining alternatives, encouraging me to stay open-minded, to think intuitively, and to allow ideas to grow before they are constrained by technicality.

For me, the “futuristic” aspect of MAD’s language does not lie in its appearance but in its courage: the courage to rethink what a building can be, how it can shape perception, and how it can reconnect people with both the physical and the spiritual dimensions of nature.

FM42: With an Executive Master in Innovation, you’re exploring how AI can enhance architectural workflows. In your view, which aspects of the

design process benefit most from AI-driven methods?

Chiara Ciccarelli: I’m really passionate on AI and how it is already changing architect’s workflow. In my experience, as many experts are also underlining, AI is most valuable when it amplifies the architect’s ability to explore, iterate, and make informed decisions, not when it replaces creative thinking. In my work, we use AI especially in the early and mid-stages of design.

In my experience, AI is extremely effective for what we call the quick and dirty phase of design (generating early visualizations, atmospheres, or rapid variations that help me clarify a direction). These tools expand and accelerate imagination, but they should never replace architectural thinking (and it becomes dangerous when they start to). They don’t understand construction logic, sequencing, or the real constraints of a project. A model might produce a beautiful image, but it won’t solve issues of function, structure, or detailing.

That’s why I see AI not as a shortcut, but as a companion that expands the front end of the creative process. The real potential lies not in pretending AI can design buildings on its own, but in building tools that amplify what architects already do well. That’s why, I believe architecture could benefit from AI systems trained on our own modelling workflows, geometric principles, and design languages.

If we can codify certain patterns (the way we articulate space, handle transitions, or structure form — then AI becomes more than an image generator; it becomes a collaborator that understands the grammar behind our decisions. This is where I see the future: using AI the way developers use language models, as a structured assistant that helps us design more intelligently, not more superficially.

So for me, AI enhances the process when it supports precision, exploration, and dialogue — not when it tries to imitate architecture without understanding it.

FM42: You specialize in concept storytelling and installation-based experimentation. How do these skills influence the way you communicate ideas within a large, concept-oriented studio like MAD?

Chiara Ciccarelli: Working in a large studio means constantly turning abstract intuitions into clear visual and verbal communication—through sketches, diagrams, quick models, or concise narratives. In a concept-driven environment like MAD, this ability is essential: the initial idea often becomes the compass for the entire design journey, so it needs to be understood immediately and intuitively.

My background in installation work has strengthened this skill. It taught me to experiment quickly, prototype atmospheres, and build spatial fragments that allow others to enter the idea rather than simply observe it. This approach helps transform a concept into an experience that can be shared, discussed, and developed collectively.

Ultimately, these tools allow me to act as a connector between intuition and delivery. They help translate MAD’s conceptual ambitions into stories and experiential frameworks that guide the team from the first gesture to the built form

FM42: What do you believe will define the next era of architecture, and where do you see your own work evolving within that future?

Chiara Ciccarelli: I believe the next era of architecture will be defined by an expansion beyond the discipline as we traditionally know it. Architecture has been constrained by regulation, functionality, and by a modernist narrative that once shaped society but now struggles to keep pace with the speed and complexity of contemporary life. Today, architecture can no longer rely only on its own tools or frameworks, indeed it needs to open itself to other fields and learn to speak their languages.

In my opinion, we live in a moment where society moves faster than our policies, our instruments, and often our imagination. People discuss geopolitics, AI, climate instability, and cultural displacement far more than they talk about buildings. This disconnect reveals something essential: architecture must move into new territories and regain cultural, emotional, and ethical relevance.

I see the future of architecture as interdisciplinary, experiential, and deeply more-than-human. This means understanding that the built environment is not designed only for humans, but for the broader ecological systems, species, and material agencies that share and shape our world. The next era will require architects to consider relationships—between humans, non-humans, and environments—rather than focusing solely on objects or forms. It will blur into fields like technology, material science, digital fabrication, narrative, and even performance or psychology. Architecture will need to speak again to people’s inner lives, not only through form, but through meaning. It should act as an innovation of meaning.

For my part, I see my work evolving at the intersection of innovation and emotional experience: using tools like AI to expand our creative vocabulary, while ensuring that design remains fundamentally human in intention and more-than-human in awareness. I’m interested in architectures that are not just built objects, but cultural interfaces—places where people can feel connected, inspired, or transformed, and where non-human actors are not an afterthought but part of the design narrative.

If the last century was about standardization and control, the next one will be about fluidity, hybridity, and reconnection—with nature, with culture, and with the unseen dimensions of our world. In a sense, architecture must become antifragile, in the way Nassim Nicholas Taleb defines it: not merely able to withstand uncertainty, but capable of growing through it, using complexity as a generative force rather than something to resist.

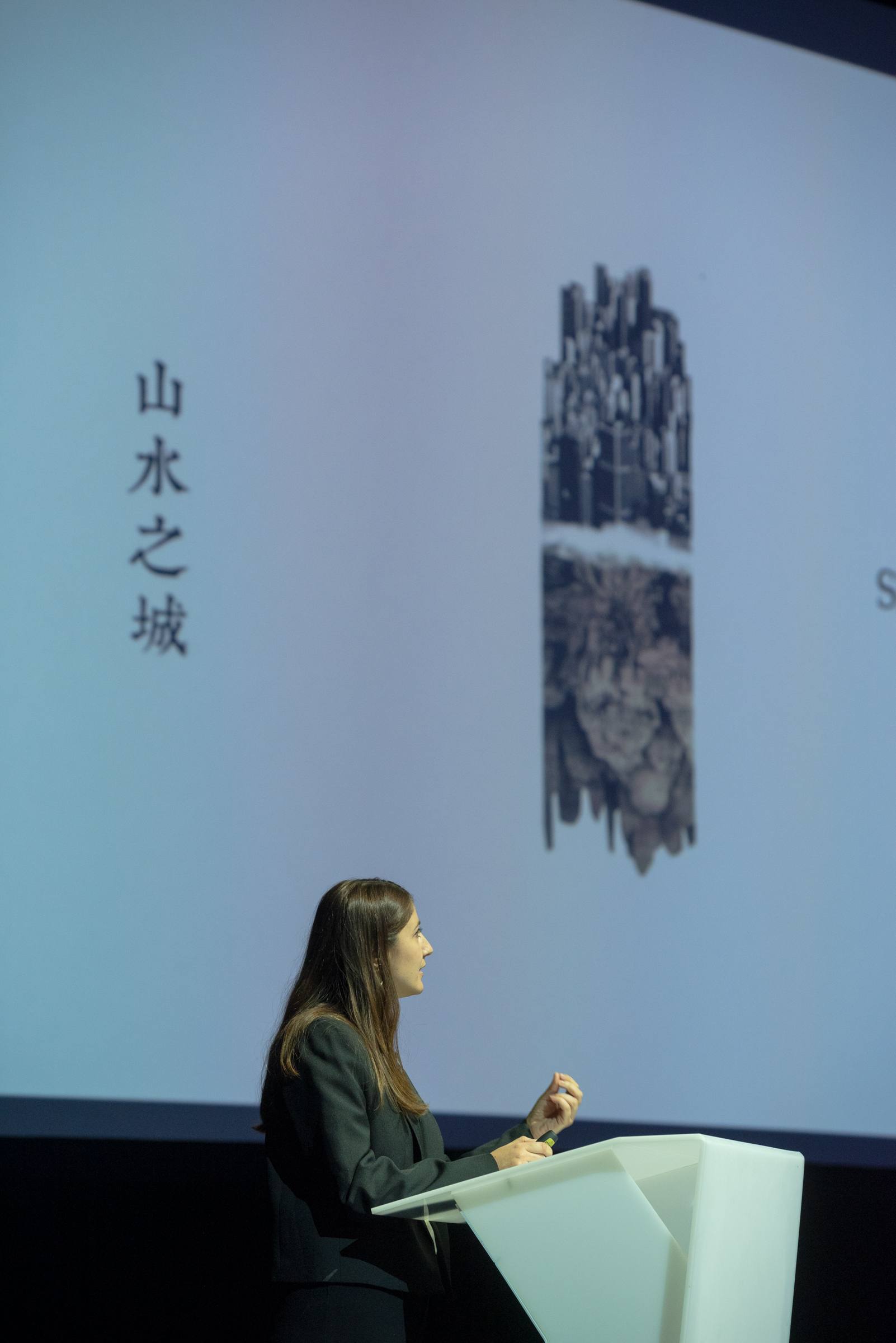

FM42: At the Architect Forum, you spoke about “Futurism Rooted in Nature.” How do you see this balance between advanced technology and natural principles shaping the future of architectural design?

Chiara Ciccarelli: For me, the future of architecture lies in combining technological intelligence with the deeper logics of the natural world. Advanced tools like AI, sensing systems, and new materials allow us to push boundaries, but they become meaningful only when they reinforce a more ecological, interconnected way of thinking.

This balance points toward a future where architecture is not just for people, but grows with its environment — responsive, adaptive, and part of a larger living system. It’s a direction that resonates with the spirit of Futurism Rooted in Nature: understanding architecture as a catalyst within a broader network of agents, energies, and ecologies.

In this sense, futurism rooted in nature is not a style but an attitude — one where technology amplifies our capacity to imagine buildings that are intuitive, sensitive, and aligned with the dynamics that shape our planet.