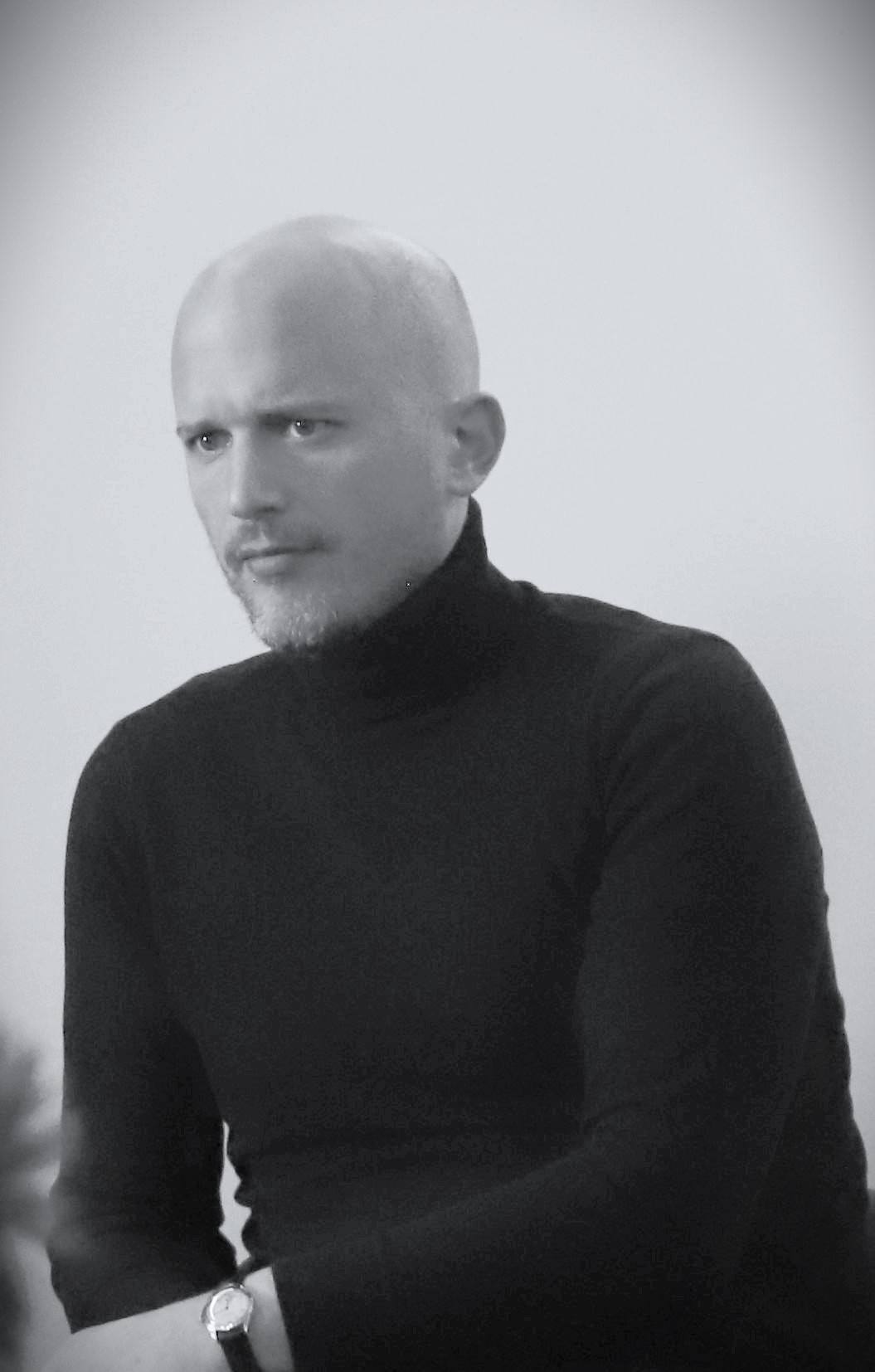

Clément Blanchet, founder of CBA, is celebrated for his innovative, human-centred approach to architecture and urban design. His work turns complex urban challenges into clear, functional, and meaningful projects.

In this interview, he shares his studio’s philosophy, insights for young architects, and reflections from the workshop he led at the Architect Forum in Belgrade.

FM42: Can you tell us about CBA’s philosophy and what makes your work instantly recognizable? Is there one project that really defines your studio’s identity?

Clément Blanchet: At CBA, our philosophy is all about extracting originality from the context. We believe architecture doesn’t always have to shout; it can be quietly radical by engaging deeply with everyday life. In practice, we operate like a kind of laboratory – testing ideas, collaborating across disciplines, and challenging norms. This means our design process is very contextual and human-focused: we start with real urban issues or cultural patterns and transform them into architectural clarity. Our work tends to be recognizable not for a single style or shape, but for a certain approach – a clarity of concept and a respect for the environment and community. We often strive for designs that resist the expected trends or egos of architecture and instead embrace collective needs. This gives our projects a common DNA of being rational yet bold, modern yet responsive to their place.

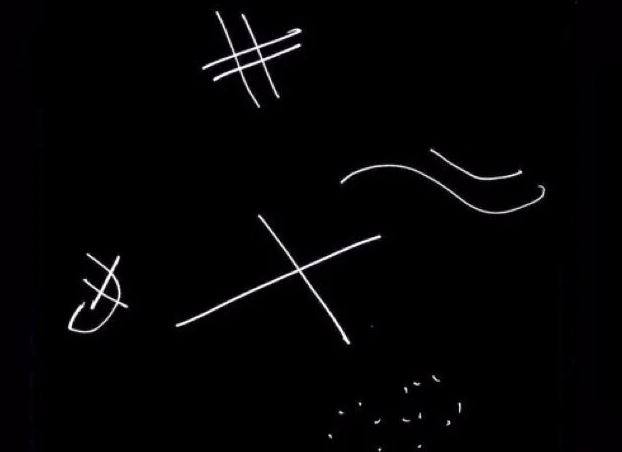

We do not have one project representing CBA, however I often cite as defining our identity is the Alexis de Tocqueville Library in Caen. Its design embodies our core values. We conceived it as an “agora of ideas” – the building is shaped like a large X or cross, with each wing pointing to a key part of the city and housing a distinct realm of knowledge. Where those wings intersect, a transparent central forum brings people and disciplines together. In other words, a very simple, almost ordinary gesture – two lines crossing – generated a powerful civic space. That library is a symbol of what we stand for: lateral thinking in architecture, the idea that a design can simultaneously connect to history, geography, and community. We didn’t pursue an extravagant form for its own sake; we allowed function and context to shape the form, which in turn created something unique. The result is a modern library that opens itself to the city on all sides, inviting interaction and giving Caen a new public heart. It’s a project that proved how embracing an ordinary solution (like orienting toward city landmarks and everyday users) can produce an extraordinary urban effect.

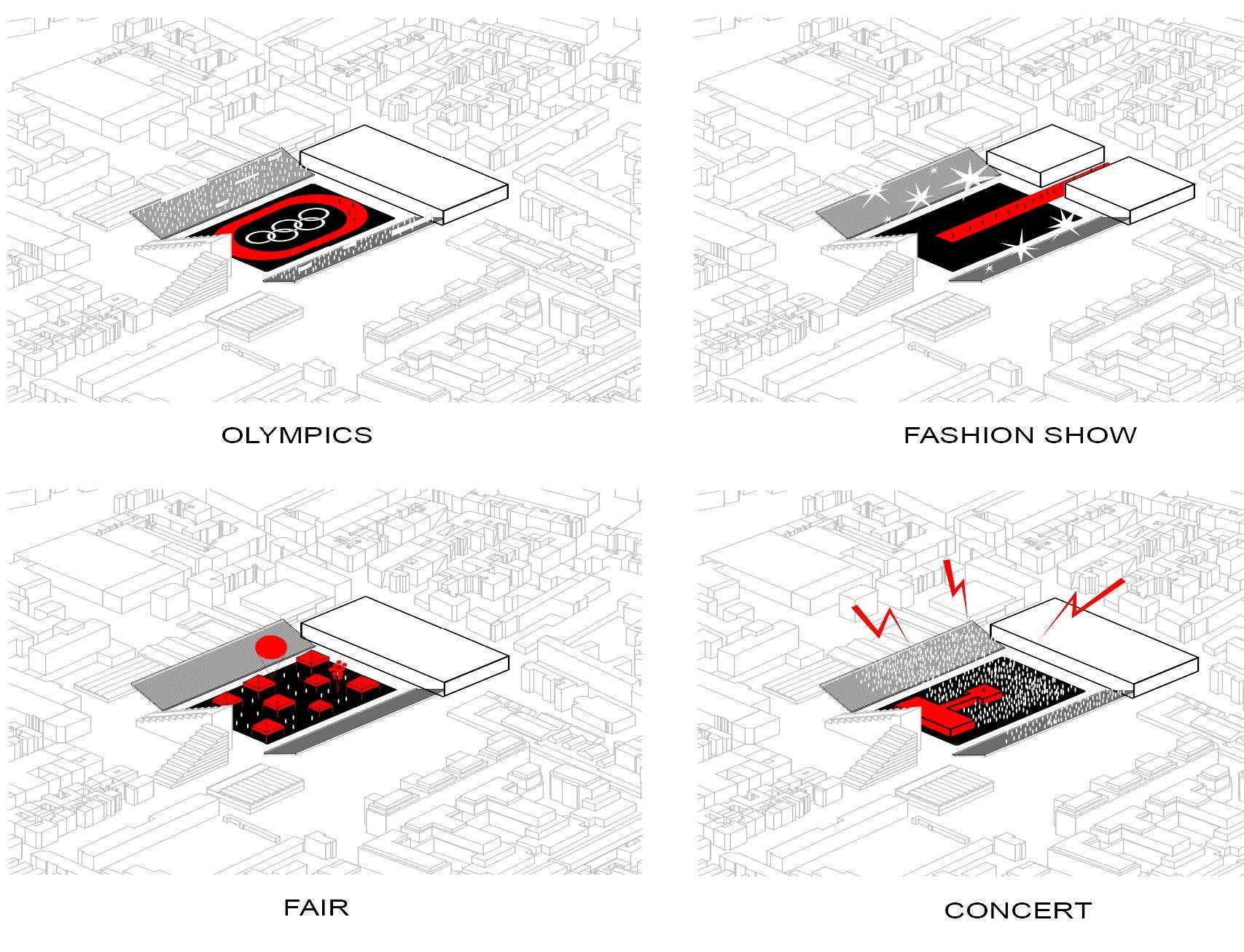

Another example is our Bauer Stadium project in Saint-Ouen. There, we took a historic football stadium and reimagined it as a piece of city infrastructure, not an isolated object. We designed the complex to blend into the neighbourhood’s fabric with a brick base echoing local architecture, and we literally made the stadium a mixed-use urban hub – including shops, cultural spaces, even a rooftop bar. In fact, we proposed that it could host more than just football games but also concerts and even fashion shows on the pitch. This idea of a stadium open 365 days a year, where the stadium becomes the city and the city becomes the stadium, captures our ethos. We love designs that dissolve boundaries: between building and city, between one program and another. In all our projects – whether a library, a school, a bridge, or a stadium – we try to inject that clarity of concept and openness to the urban context. That consistent mindset makes a CBA project recognizable more by experience and intent than by any stylistic signature.

One other project emblematic of CBA’s identity is the new Istituto Marangoni Design School campus in Paris (pictured below). It transforms a historic 19th-century structure by weaving in bold contemporary forms, creating a dialogue between old and new. The design organizes the school around a central courtyard, using features like a sculptural open-air staircase and external walkways as social spaces for students. The result is more than just a building – it’s “an invitation to push creative boundaries” and a contribution to Paris’s reputation as a capital of fashion and innovation. This project really embodies our studio’s DNA: it’s contextually sensitive, openly modern, and designed around the user experience, which in this case means inspiring the next generation of designers. We’re proud that it captures our vision so well, blending heritage with forward-thinking design in a human-centered way.

FM42: What would you say young architects need to know or focus on today?

Clément Blanchet: The world is changing rapidly, and young architects must be ready to engage with this complexity head-on. My advice would be to focus on a few key principles:

Stay curious beyond architecture: Don’t design in a bubble. Immerse yourself in understanding cities, people, and the forces shaping society – from technology to politics to climate. Architecture today is intertwined with many fields, so a broad cultural and scientific curiosity will make your designs richer. In practice, this means listening to other experts and to the public. Be prepared to act as an anthropologist and an urbanist, not just a stylist. The best architecture comes from understanding real human behaviors and needs, not from chasing glossy magazine images.

Embrace the ordinary and the context: Rather than aiming to create instant icons, learn to find inspiration in everyday life and local context. Solve real problems – improve a street corner, bring light into a dense neighborhood, reuse a forgotten structure. If you can respond to the ordinary constraints of a site in an elegant way, you will achieve something original. I often say architecture should not always be about being extraordinary, but about being meaningful within its community. Young architects should resist the temptation to design for ego or headlines. Instead, focus on how your work can quietly improve daily life and social cohesion. Paradoxically, that grounded approach often leads to the most innovative outcomes.

Keep learning and collaborating: The architect’s role is evolving – we are no longer lone master builders; we are coordinators of many disciplines. So never stop learning. Whether it’s new digital tools (parametric design, AI, etc.) or sustainable materials, stay open to acquiring new skills. Likewise, work with others: engineers, sociologists, ecologists, artists. A multidisciplinary approach will elevate your work. For example, in my own studio we treat projects as research, engaging diverse “actors” to inform the design. Young architects should be prepared to constantly expand their knowledge and adapt – this flexibility is crucial today.

Build with purpose and responsibility: Finally, focus on the big challenges of your generation. We face climate change, urban inequality, and fast technological shifts. Architecture is not just about pretty buildings; it’s about shaping society. So put sustainability at the core of your thinking – every project should respect the environment and seek to reduce its footprint. Likewise, think about social impact: design inclusive spaces, affordable housing, and resilient cities. If you ground your work in purpose and ethics, it will stand the test of time.

Young architects need to combine idealism with pragmatism. Dream big about making the world better, but ground those dreams in a real understanding of context and human needs. Learn to turn constraints into design opportunities, because that skill is more valuable than any glossy rendering technique. And remember that architecture is a long conversation across time – stay humble, keep learning, and contribute something positive to that ongoing story.

FM42: How was your experience leading the workshop at the Architect Forum in Belgrade?

Clément Blanchet: It was a truly inspiring experience. The workshop in Belgrade brought together an energetic group of students and young professionals, and their enthusiasm was contagious. The theme of the forum was “Vision – Shaping Architecture’s Next Era,” which set an ambitious tone. As the workshop leader, I encouraged participants to question assumptions and imagine bold ideas for the future of cities. What struck me was how eagerly they engaged with this challenge. We had teams from different backgrounds collaborating, sketching, debating – it felt like a microcosm of what the next generation of architects will be like: open-minded, collaborative, and not afraid to mix disciplines.

Belgrade itself added a special context. It’s a city with a complex history and a vibrant urban fabric, so there was a palpable sense of place and identity that the students drew upon. I was impressed by how they proposed solutions that blended local insight with global thinking. For example, some workshop ideas addressed very contemporary issues – like reusing post-industrial structures or integrating nature into dense neighbourhoods – but in ways that resonated with Belgrade’s unique character. That showed me these young architects understand the importance of context, even as they reach for innovative forms.

Personally, leading the workshop was also a learning experience for me. It was refreshing to step into an academic-atelier mode, where hierarchy fell away and we were just a room full of curious designers exchanging ideas. I shared some of CBA’s approaches and my concept of finding the “originality in the ordinary,” and it was rewarding to see how the students ran with that. They weren’t interested in flashy “starchitect” visions; they were really trying to grapple with making cities more livable and sustainable – which gives me a lot of hope. The collective energy and creativity in that room reaffirmed my belief that the future of architecture will be shaped by collaboration and continuous learning.

By the end of the workshop, I think we all – myself included – came away with a richer perspective. We discussed not just design techniques but also the architect’s role in society. I remember a moment where a student asked about balancing cultural heritage with modern needs (a very real issue in Belgrade). It led to a great discussion about “resisting nostalgia” while still valuing history – a balance that is crucial everywhere. Those kinds of dialogues made the event meaningful. My Belgrade experience was overall invigorating. It reinforced why I enjoy teaching and mentoring: because it’s a two-way street. Guiding young talents also renews my own inspiration. I left feeling optimistic about what the next era of architects will bring – they are visionary yet grounded, exactly what our cities will need.

FM42: What currently excites or inspires you most in architecture worldwide?

Clément Blanchet: I’m very optimistic about where architecture is heading, because I see several exciting shifts happening around the world. One major inspiration for me is the way architecture is blurring boundaries – between different functions, between building and city, and even between disciplines. We’re moving past the era of singular iconic objects, and towards more hybrid, flexible designs. For instance, I love seeing projects where a building isn’t just one thing. Take our Red Star Stadium project as an example: it’s not only a sports venue, but also imagined as a venue for concerts and even fashion catwalks. That kind of multifunctional thinking – where a stadium can double as an urban plaza or a library can serve as a community center – really excites me. It means architecture is becoming more open-ended and democratic, serving multiple uses and users over time.

I’m also inspired by the global push for sustainability and reconnecting with nature in design. There’s a growing awareness that architecture must work with the environment, not against it. All around the world, I see architects using local materials, passive design strategies, and green systems in ingenious ways. From wooden high-rises in Scandinavia to vertical gardens in Asian megacities, sustainability is sparking creativity. In our own projects, we take this seriously – for example, in the new Administrative Centre we designed in Sicily, we integrated Mediterranean vegetation and natural cooling strategies right into the architecture. The roof becomes a hanging garden and public terrace, so building and landscape merge. This trend of weaving ecology into architecture – making buildings that breathe, that produce energy, that harmonize with their climate – is something that gives me hope. It’s not just about technology, but a mindset change in the profession.

Another thing that inspires me is the resurgence of adaptive reuse and urban regeneration. Instead of constantly building new, there’s creativity blossoming in transforming the old. Converting disused factories into cultural centres, old offices into housing – these projects not only recycle materials, they also tie into the story of a place. I see this everywhere: architects treating cities as living organisms that can heal and adapt. It’s a very sustainable and culturally rich approach, and it produces wonderfully unique spaces that a new build could never replicate. Our recently completed Istituto Marangoni campus in Paris followed this path – we took a 19th-century building and surgically inserted modern elements to create a design school, preserving the soul of the old structure while making it cutting-edge for today’s needs. Such projects show that innovation isn’t always about a wild new form; it can be about a clever reinterpretation of what’s already there.

Finally, I have to say I’m excited by the expansion of architecture’s toolkit and reach. Digital tools like computational design, AI, and big data are opening possibilities we couldn’t imagine a decade ago. We can simulate entire microclimates or optimize structures in seconds – that’s fascinating. But equally, I’m inspired by how architects are applying their skills beyond traditional practice – engaging in humanitarian work, shaping public policy, or addressing social issues. The field is more fluid and interdisciplinary now. For example, many young firms are mixing architecture with research, activism, or product design. There’s a crossover with fields like fashion, film, and technology that produces fresh perspectives. This cross-pollination means architects are learning to think in terms of systems and networks, not just isolated buildings (seeing buildings as part of a larger social-natural network). We’re seeing architects design not just physical spaces, but experiences and strategies.

All these trends – boundary-blurring, sustainability, adaptive reuse, interdisciplinary practice – point to a more holistic vision of architecture. It’s no longer just about who can design the most eye-catching museum; it’s about who can meaningfully improve the urban habitat. That shift inspires me every day. There’s a global generation of architects and designers now who care deeply about impact, and they’re coming up with ingenious ways to deliver it. Whether it’s a humble community project in a developing country or a high-tech experimental building in a capital city, I find myself learning from all of it. The dialogue is truly global now, and inspiration comes from everywhere – a clever housing solution in Latin America can influence a project in Europe, and vice versa. As someone who thrives on ideas, this is a wonderful time to be in architecture. The challenges we face are huge, but the creativity and collaborative spirit I see worldwide give me genuine optimism for the future of our built environment.

FM42: If you could imagine the city of the future, what would it look like?

Clément Blanchet: When I imagine the city of the future, I see a place that might appear surprisingly ordinary at first glance, yet is teeming with originality beneath the surface. I don’t think the future city will be a science-fiction fantasy of flying cars and gleaming skyscrapers. Instead, it will be a more human-centred, adaptable, and ecologically integrated environment – a city that feels alive and inclusive. In practical terms, the city of tomorrow will blur many of the boundaries we take for granted today. Greenery will no longer be an afterthought; it will be woven through the urban fabric.

I also see the future city as highly flexible and responsive. Rigid zoning – where one district is only for offices, another only for housing – might fade away. In its place, we’ll have more fluid neighborhoods that mix living, working, learning, and leisure seamlessly. Thanks to technology and new lifestyles, a single space could transform throughout the day. For example, a public plaza might host a farmers’ market in the morning, serve as an open-air co-working space in the afternoon, and turn into a concert or fashion runway in the evening. Architecture will provide adaptable frameworks for these changing uses. This is an idea we already explored with the Bauer District project – making a stadium and its surroundings a multi-purpose urban quarter, not a single-use monolith.

I think future cities will be full of such hybrid places, where infrastructure doubles as social space. Mobility will change too: with autonomous vehicles and better public transit, we may reclaim a lot of street space currently given to cars. Imagine more pedestrian promenades, bike highways, and plazas where once there were parking lots. The city might actually slow down in the best sense – prioritizing walkability, human interaction, and experience over frantic car traffic.

Crucially, the city of the future will be inclusive and participatory. I believe our future urban environments will be co-created with the people who live in them. We already see trends of community engagement in design – this will become the norm. Citizens might help design their own housing (perhaps through customizable modular systems), or vote on the kind of public spaces they want. This social aspect is important: a city is not just physical; it’s also a tapestry of culture and relationships. So I imagine a future city that celebrates local identities and diversity. It won’t be a one-size-fits-all global city of identical towers – rather, each city will leverage its unique heritage and mix it with modern innovations. In a way, the future city could look familiar because it will preserve what we love about our cities (the historic streets, the gathering places, the human scale), but it will function in a smarter, more sustainable way. It will be hyper-connected through technology – sensors monitoring energy use, apps helping citizens engage with services – yet this tech will be mostly invisible, quietly enhancing daily life rather than overwhelming it.

To sum up my vision: the city of the future is like a living organism. It breathes (with green lungs of parks and gardens), it circulates resources efficiently, and it continuously adapts to the needs of its inhabitants. It’s a place where architecture provides the stage for human life in all its richness – where a stadium can be a public square, a library can host a hackathon, a bridge can shelter a marketplace. In such a city, “ordinary” moments (like walking to work, or sitting in a courtyard) are enhanced by thoughtful design to become pleasant and meaningful. We often talk about smart cities in terms of technology, but I think the smartest cities will also be emotionally and culturally intelligent. They will foster community, creativity, and well-being. They might even reintroduce a bit of serendipity into urban life – those chance encounters and discoveries that make city living exciting.

In the city of the future, we architects might be less visible as signature designers, but more like choreographers of urban experiences. Our job will be to set up adaptable frameworks and let the life of the city fill them in, rather than dictating every outcome. I find that prospect liberating. It means the city can continually reinvent itself without losing its soul. In a way, it circles back to our mantra: finding originality in the ordinary. The future city will take the timeless needs of human life – meeting, learning, playing, and dwelling – and fulfill them in original ways that also respect our planet. It’s a city I would love to live in, and it’s the vision that quietly guides the work I do today, one project at a time.

Ph credits: Promo CBA